I’m standing in front of a vending machine on the third floor of the English Philosophy Building at the University of Iowa, in November 1975. I’m a sophomore, in my first semester as an English major. Standing beside me is my very first writing professor, a man who inspires and intimidates me, the two perhaps comingled, bushy eye-browed, wearing a heavy cotton blue and white striped shirt, sleeves three-quarters rolled. “He’ll judge what I buy,” I think, and the judgment matters somehow. So I buy a box of raisins, strange choice for me, and offer him some, shaking into his palm. He makes a small-talk comment, and I feel as though I’d received Isaac’s blessing. It is a momentously silly thing.

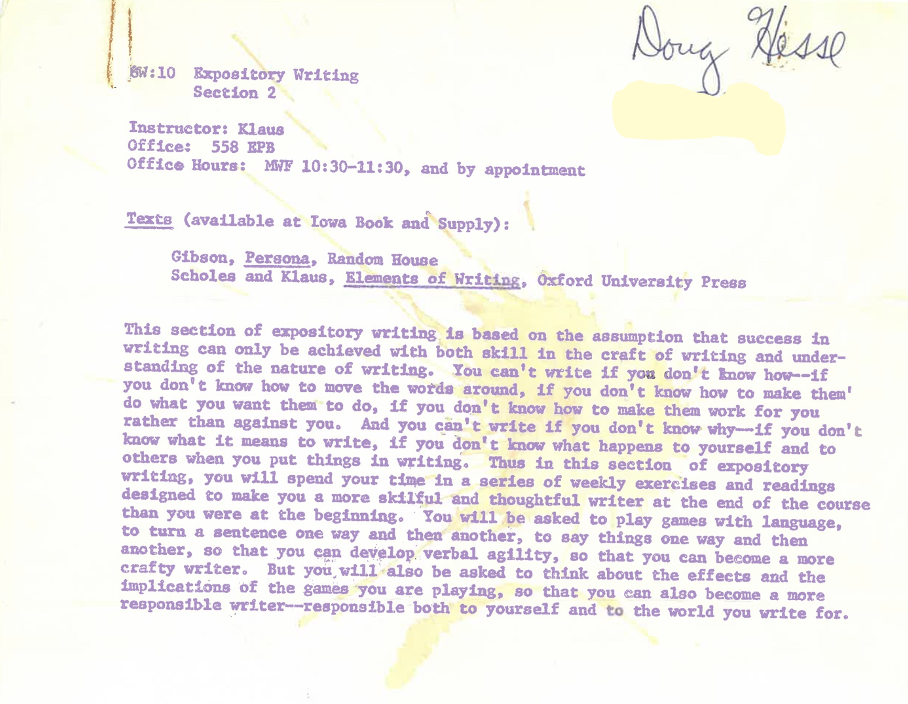

Carl Klaus was my first writing teacher and, with Susan Lohafer, one of the two best. The first course I took as an English major, having given up chemistry when I figured someone making B’s in a subject matter ought to understand what he was doing, was Carl’s 8W:10 Expository Writing, and the texts were Walker Gibson’s Persona and Scholes and Klaus’s Elements of Writing, a slender book on style and effect that included grand 16th and 17th century periodic sentences by writers like Hooker, Brown, and the like. We spent the whole first class talking about a single sentence and doing things to it, adding, subtracting, substituting, rearranging: “Revision, in its root sense, means to see again.”

Our first homework assignment was to produce four revisions of that sentence, and then write an extended commentary on the effects of each version and how it achieved them. I copied my final version in my best penmanship in blue ink on lined paper, and a week later, Carl returned a half page of typewritten comments about my comments, reading me as closely, it seemed, as we’d read that sentence.

In that first exchange, I grasped that there was something inexhaustible about writing and about language, something important and holy. I found what I wanted to do with my career.

I took more classes with him as an undergraduate and as a student in the nonfiction MA program. Among them was his magisterial “The Art of the Essay,” conceived and taught in the 1970s, long before creative nonfiction became fashionable in MFA programs. Addison and Steele, Charles Lamb, Virginia Woolf, George Orwell, E.B. White, James Baldwin, Joan Didion. When Philip Lopate’s anthology came out in the 1990s, I irrationally begrudged it. Klaus and his Iowa colleagues had lived there long before latecomers re-staked the land.

That element of Carl’s intimidation never disappeared, and I was perpetually awkward around him, desperately wanting to please but figuring myself not quite worthy. When I came back to Iowa for the PhD in the mid 1980’s, I wrote a dissertation about narrative strategies in essays, 18th century to the present, The Story in the Essay. Carl would have been the obvious person to direct it, but I knew he’d expect so very much—reasonably so but more than I could then give with a wife, a four-year-old and a one-year-old living in a cement block apartment. So I asked Susan instead, with Carl on the committee. Susan was terrific, of course, but I think over the years how I might have come differently through Carl’s refining fire.

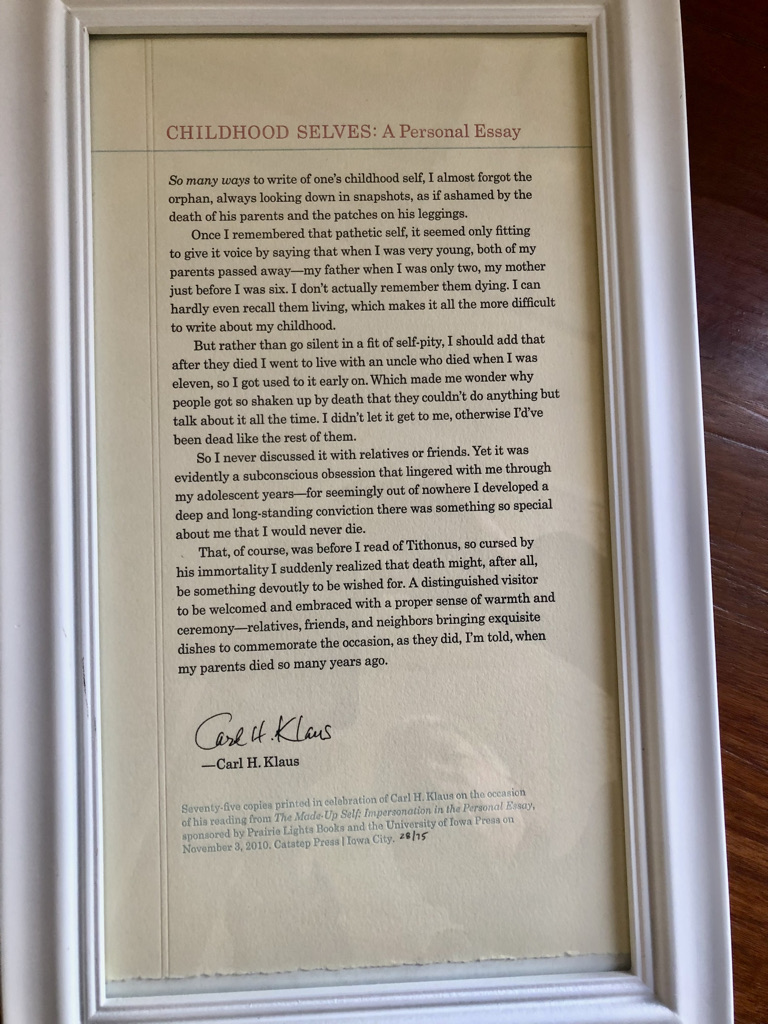

It’s been nearly a dozen years since I was physically with Carl, though I’ve been many times with his five books published since then, with his emails, and with his spirit. In November 2010, he was reading from The Made Up Self at Prairie Lights in Iowa City. They’d printed seventy five broadsides for the occasion, a very short essay, five paragraphs (nothing was by chance with Carl), “Childhood Selves: A Personal Essay.” I purchased #28, and it has hung above my desk since then. It’s a sober essay, intensely personal and yet oddly removed, talking about his having become an orphan at age six. At one point he realizes that “seemingly out of nowhere I developed a deep and long-standing conviction that there was something so special about me that I would never die,” only later to come to the more profound realization that “death might, after all, be something devoutly to be wished for. A distinguished visitor to be welcomed and embraced with a proper sense of warmth and ceremony—relatives, friends, and neighbors bringing exquisite dishes to commemorate the occasion, as they did, I’m told, when my parents died so many years ago.” He thus ends with long, eloquent sentence fragment, an afterthought, it seems, but with the profoundest punch. Completely finished.

Carl died February 1, 2022. Many of us really thought he’d never die, could never die: He was too important to our formations and identities as writers and writing teachers, to our lives. He has burned in the hallways and backrooms of my own prose nearly fifty years. You will forgive me if his death seems less like a distinguished visitor than like a rude thief taking an exquisite life.

Iowa City, November 2010.