This morning I was reminded (I won’t go into why) of a talk I gave at the Conference on College Composition and Communication in 2000. Some conditions I was addressing nearly two decades ago have changed, but the failure persists to recognize that certain areas of higher education have long taken teaching very seriously. Chief among them is composition studies. 4/8/18 DH

Writing Programs as Squanto, Welcoming the Tall Ships of Teaching Reform

Douglas Hesse

Conference on College Composition and Communication

Minneapolis

April 2000

Higher education has discovered teaching. There are, surprise, students in classrooms, and students are, just maybe, complicated subjects. There are, surprise, ways of teaching beyond having students listen, read, and report. There might be, surprise, some need for college teachers to know theory and research on teaching. And just maybe this knowledge and experience and ability could actually count in tenure and promotion. People who have discovered all these things range from deans to trustees to, even, a recent president of the Modern Language Association.

This last person declared in a July Chronicle of Higher Education article that, “Everyone complains these days that we don’t train graduate students to teach, but no one ever seems to do anything about it” (Elaine Showalter). Apparently, “no one” includes the hundreds of writing program directors around the country who for decades have mentored new teachers, led preservice workshops, taught courses in composition pedagogy, published articles on teaching writing. I repeat her claim: “Everyone complains these days that we don’t train graduate students to teach, but no one ever seems to do anything about it.” In contrast, this author has been brave, has forged a new path through the virgin pedagogical wilderness of English studies; her bibliographic breadcrumbs are twelve books, all of them generically about teaching, only one (by Jane Thompkins) even from the broad field of English studies. One speculates that, for this writer, publishers like NCTE or Boynton/Cook Heinemann do not exist.

By you have caught my tone and rightly fear that you’re in the presence of a polemic.

So let me get the worst out of the way and put my argument in a nutshell. As departments, colleges, institutions, and governing boards “discover” teaching, they are like Columbus discovering America, replacing cultures of teaching that already exist, especially within composition studies. New sites for the promotion of pedagogy emerge, things like Centers for Teaching Excellence. General education reforms address not only the “what” of course requirements but also the “how” of pedagogy.

Leading many of these efforts are writing programs and their directors, who after all have long lived on the land of teaching. I liken us to Squanto, the “good Indian” from my sixth grade social studies class, who helped the Mayflower Pilgrims, people so clueless they didn’t know enough to toss dead fish or manure among the planted corn. At least that’s what I remember. But even as writing programs show their savvy and warm hearts, I fear that our leadership will ultimately go unrecognized or forgotten. To put it most strongly, because of the historical devaluation of writing programs, the knowledge of teaching located within those cannot count as “real” knowledge.

At several “prestigious” universities either there is no freshman writing requirement or there is no extensive development program for those assigned to teach in it. If you are a notable personage within English studies who happens to teach at such an institution, it is relatively easy—and extraordinarily self-interested—to declare that “no one ever seems to do anything” about teaching. The recent celebration of teaching, then, ironically functions further to marginalize composition studies, whose historical identity has been entwined with pedagogy.

At this point, I know I should qualify things. What is the difference between PhD-granting and non-PhD granting institutions, between historically strong and active writing programs and mere place holders, between large schools and small? How do arguments about abolishing the universal freshman writing requirement intersect with this general education reform? And, most importantly, why should we care? I mean, is it just a matter of ego that that composition studies should get credit for having been concerned about teaching apparently long before other disciplines have been?

I’ll tell you why I do care, but I’ll do it obliquely, focusing on just one site of contention, the increasingly emergent freshman seminar courses.

By the mid 1990’s, over 720 American colleges and universities offered some kind of freshman seminar. These seminars fall into four main types. The most common are “extended orientations,” usually for one credit, and concentrate on advising, introducing campus resources such as the library or counseling center, exploring careers and so on. A second type of seminar deals with basic study skills: time management, campus policies, note taking, and so on. The third and fourth types are broadly characterized as “academic seminars,” usually three or more credit courses concentrating on some interdisciplinary topic, perhaps including some orientation or study skills components but really focusing on a theme or issue. Such seminars have been around for decades, especially at liberal arts colleges. Sometimes they exist in conjunction with required composition, sometimes instead of it. A liberal arts college about a dozen blocks from my own office discarded freshman writing a few years ago, for complex reasons including a perception that not having freshman writing enhanced the prestige of the place.

What I now find interesting, though, is the slow movement at some larger universities to institute such courses. There are complicated reasons why, but I want to sketch three of them. The first is a movement channeled through organizations like AAHE and AAC&U to improve the quality of the undergraduate experience. Calls for student-centered classrooms, interactive inquiry-based learning, and process-directed teaching are familiar to us in composition studies. Their motivations are a mix of intellectual altruism, yes, but also an economic pragmatism whose fuels are retention, legislative and governing board funding, and a suspicion of “lazy” professors who ought to teach more to earn their keep.

The Boyer Commission’s report on Reinventing Undergraduate Education is a convenient distillation of many of these ideas. In addition to an Academic Bill of Rights, the report suggests ten ways to change undergraduate education. Of particular interest is number five: “Link communication skills and course work.” Listen to this recommendation:

“The freshman composition course should relate to other classes taken simultaneously and be given serious intellectual content, or it should be abolished in favor of an integrated writing program in all courses. The course should emphasize explanation, analysis, and persuasion and should develop the skills of brevity and clarity. . . . Writing courses need to emphasize writing ‘down’ to an audience who needs information, to prepare students directly for professional work” (25).

Now, this is quite a remarkable recommendation. I could say much about the view of writing embodied here, especially the utilitarian values signaled by brevity and clarity and the view of writing as transmission and the direction of that transmission as always down. Apparently for the authors of this language, the values do not clash with the call for “serious intellectual content” and the implied need at least occasionally to write to knowledge peers and experts.

But more pertinent is the claim that freshman writing courses must depend on other courses because they lack serious intellectual content. I’ll acknowledge that courses at some schools do, usually because they are grounded in some untheorized curriculum of hyperformalism, the modes of discourse, or discrete arhetorical skills. But the statement implies that such is the current general state of freshman writing. More subtly the statement raises questions about the nature of “content.” Can the knowledge and practice of rhetorical strategies constitute “real content?” For the Boyer commission, the answer to this old question is apparently no.

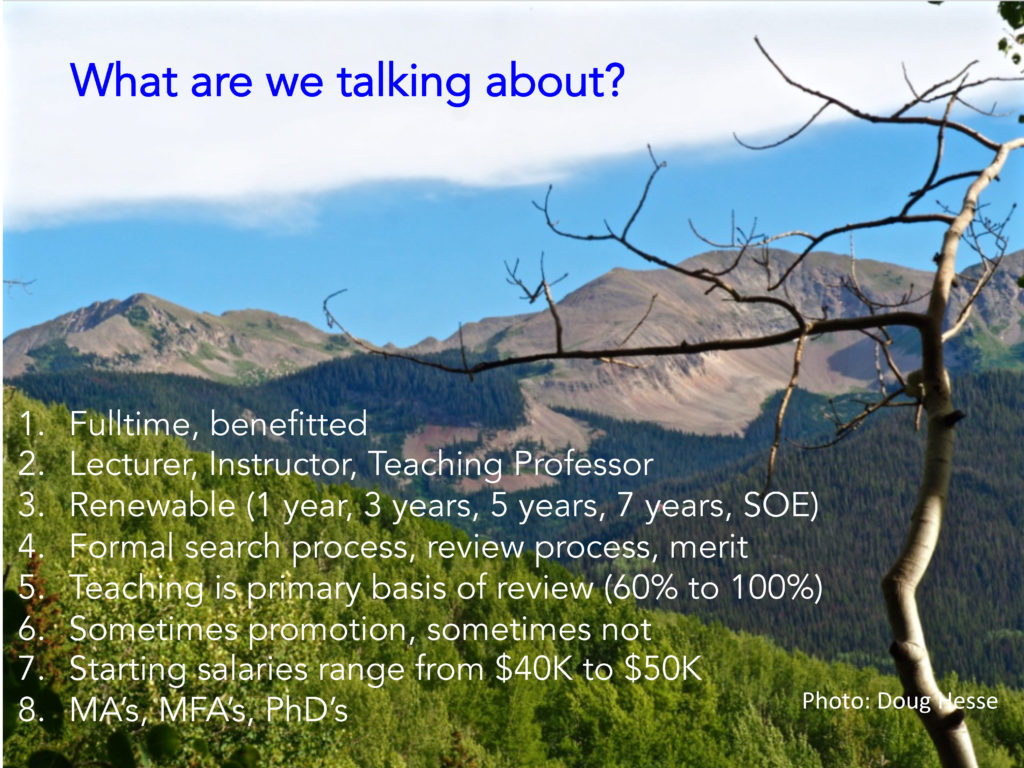

These assumptions align with a second joist for freshman seminars. Various writers have called for tempering large freshman lectures with at least some small, interactive courses. Yet the freshman writing class, which has performed such a role for decades, seems now not to count. Partly this is because writing courses presumably lack “serious intellectual content.” Partly this is because the presumably lack “real professors.” The vicious circle of this reasoning we all know well. Anyone can teach freshman writing, including faculty spouses, graduate assistants, and itinerant part-timers. The economic reasons that drive institutions to staff composition adjunctally demand that they view writing as teachable by many, unless those institutions want to be overtly cynical. Ironically, the actions of many of us who direct writing programs support this assumption. We declare the success of our training programs, justify our curricula and policies to colleagues and students, write program assessments. An even deeper irony is that as writing directors embrace alternative staffing models in the name of economic fairness, most notably in two-tiered arrangements, they buttress assumptions about writing as the work of academic primitives.

But what do faculty want to teach? This brings me to a third joist of the freshman seminar movement. Mostly they don’t want to teach writing courses as writing courses. Given several circumstances who can blame them? Except for those graduate students working centrally in rhetoric and composition studies, most continue to know little of the professional literature concerning writing and its teaching. A few may hedge their job market bets by banking a course or two, and many have experienced good TA training programs. Still, interest and respect for teaching writing is proportional to knowledge about the field. I do extensive consulting and program evaluation and regularly meet English faculty of enormous commitment and good will who nonetheless find teaching writing pure drudgework. Locked in the modes of discourse or paragraph patterns, they see the courses as important but ultimately without a single consolation.

In response, some liberal arts colleges have perhaps become bellwethers. Having no teaching assistants and having English faculty primarily trained and hired in literary studies, with perhaps one writing specialist who may or may not be tenurable and who may be in a writing center and not a department, those colleges may have little beyond tradition to support freshman composition. Alternatives like seminars, ostensibly writing intensive, have every appeal to the faculty who would teach them and to the administrators who recognize staffing flexibilities and course titles alluring to students.

Lord knows they appeal to me, too. Consider a scattered set of titles: “The Nature of Wisdom,” “A Genealogy of Freedom,” “Gender Issues in Sport,” “Time in Contemporary Music,” and so on. At a September meeting in New York on staffing in English, several of us agreed that departments were going to get more tenure line positions only if permanent faculty demonstrated a commitment to teaching freshman. As a corollary, Jim Slevin argued that faculty would willingly teach writing only if those of us in composition studies backed off from the true doctrines of the writing faith and let teachers follow their own interests. Topical freshman seminars do resonate with curricula like Bartholomae and Petroskey’s “Ways of Reading” or Bizzell and Herzberg’s “cultural cases” or any number of post process courses. But there is a significant difference between a “writing intensive” thematic seminar taught by a well-intentioned faculty member whose training consists of some faculty workshops and the same seminar as taught by someone with a professional interest in teaching writing. I wonder, though, if the difference is as substantial as it once was.

When I read a version of this paper at the MLA meeting in Chicago, Susan Miller raised a concern that neither new rhet/comp PhD’s nor old 4C’s sorts seemed much interested these days in teaching undergraduate writing. I’ve had this conversation several times in the past year, and what I think those of us who feel this way sense is a shift from writing as craft–the generating and shaping of texts for reasons aesthetic and rhetorical, grounded in linguistics–to a view of writing as a cultural phenomenon. Our graduate programs increasingly focus on what writing means rather than how writers work. I admit that mine are likely the nostalgic concerns of a generation of writing teachers schooled in the late seventies and early eighties. I note with irony that my own remarks perform the very deferral that concerns me, exploring meta issues of disciplinarity rather than being “really” about writing.

As a result of these forces, bolstered by recommendations about the nature of the freshman year, abetted by critiques of required composition from within composition studies itself, freshman seminars emerge as a way of enacting several new pedagogies: critical thinking, active learning, faculty/student process interactions, peer work, inquiry, scaffolded and sequenced assignments, all in the venue of a small course. The list is familiar to writing teachers. One way to look at this development is as the ultimate triumph of composition studies. The end of composition thus parallels Fukuyama’s declaration of the end of history, with the triumph not of democratic liberalism but of pedagogies midwifed in rhetoric and composition. In this view, the fact that composition courses might disappear for reasons of economics and redundancy would be of no concern because its values will have suffused the academy, become a spectral star child of higher education, giving up its mortal body like Bowman at the end of 2001: A Space Oddysey. But that is not my view.

I want to be clear about two things. First, I am not complaining about academic freshman seminars. I like them. I do fret about their diverting resources from writing programs, but that’s beside the larger point. Second, I have mixed feelings about the inherent desirability of mandatory freshman composition, especially as the course is likely to be positioned and staffed for the foreseeable future.

My concern is that composition’s knowledge about and commitment to teaching has been variously ignored and colonized. Perhaps, in the institutional psychology of general teaching improvement, no discipline can be perceived as having a lead; perhaps for the good of some manifest whole, faculty must imagine they are collectively inventing for the first time ideas about the nature of learning and the role language plays in it. Perhaps I should just smile slightly when colleagues across campus tell me about double entry notebooks or microthemes or writing as epistemic. Perhaps I should say thank you to the distinguished professor in my department who, teaching a freshman seminar for the first time, announces two wonderful discoveries, the portfolio and Stephen Toulmin, even as she urges her graduate students to do whatever they can to avoid teaching English 101.

But when senior spokespeople for English studies, people who by virtue of status and affiliation can command space in the Chronicle or at last spring’s summit meeting on PhD programs, declare that “Everyone complains these days that we don’t train graduate students to teach, but no one ever seems to do anything about it,” I resent it. How dare they? When such statements represent the whole state of English studies to the academic and secular world—and they do—they push composition studies ever further from higher education’s fertile river valleys of funding and prestige. As compositionists shuffle westward we may console ourselves in the cultures that grow behind us. Or we may stay and participate in something new.

The Pawtuxet Tiquantum, renamed Squanto, was kidnapped from his tribe and taken to England in 1605. He lived there until John Smith brought him back to American in 1614. But he was kidnapped again, brought to Spain, sold into slavery, then escaped to England and joined the Newfoundland company. He returned to North America in 1619. By then, his tribe had been killed by disease. He joined the settlement at Plymouth in 1621, where both his agricultural knowledge and fluency in English made him useful, especially to William Bradford during negotiations with the Wampanoags. Tisquantum died in 1622. My sixth grade social studies textbook didn’t tell the story quite that way.

I was back in my hometown, DeWitt, Iowa, over the weekend to receive a generous award from my high school alma mater. My daughter Monica surprised me from Washington, DC, and both of us sat Thursday afternoon in a sophomore English class. It was the same classroom where I took junior English 43 years ago with Mr. Raikes. I should be more precise: the classroom is in the same place, though it’s massively transformed, along with the school around it. For example, in the last century we performed musicals on the stage in the school gym, where backstage right was filled with a weight machine.

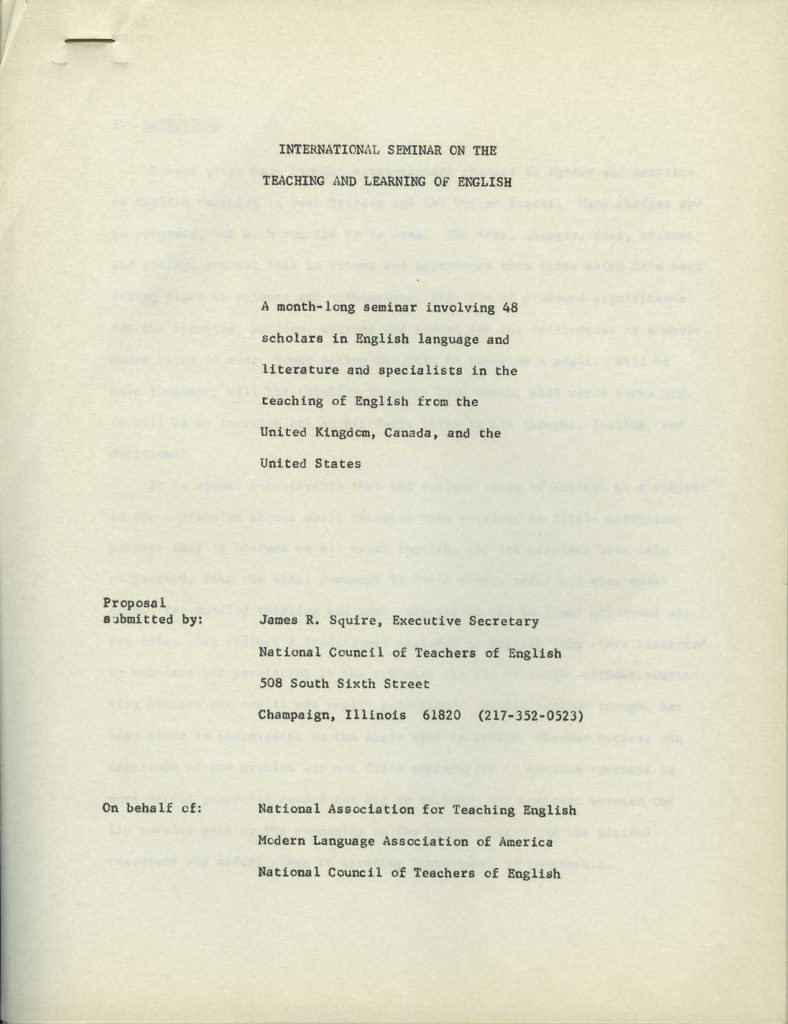

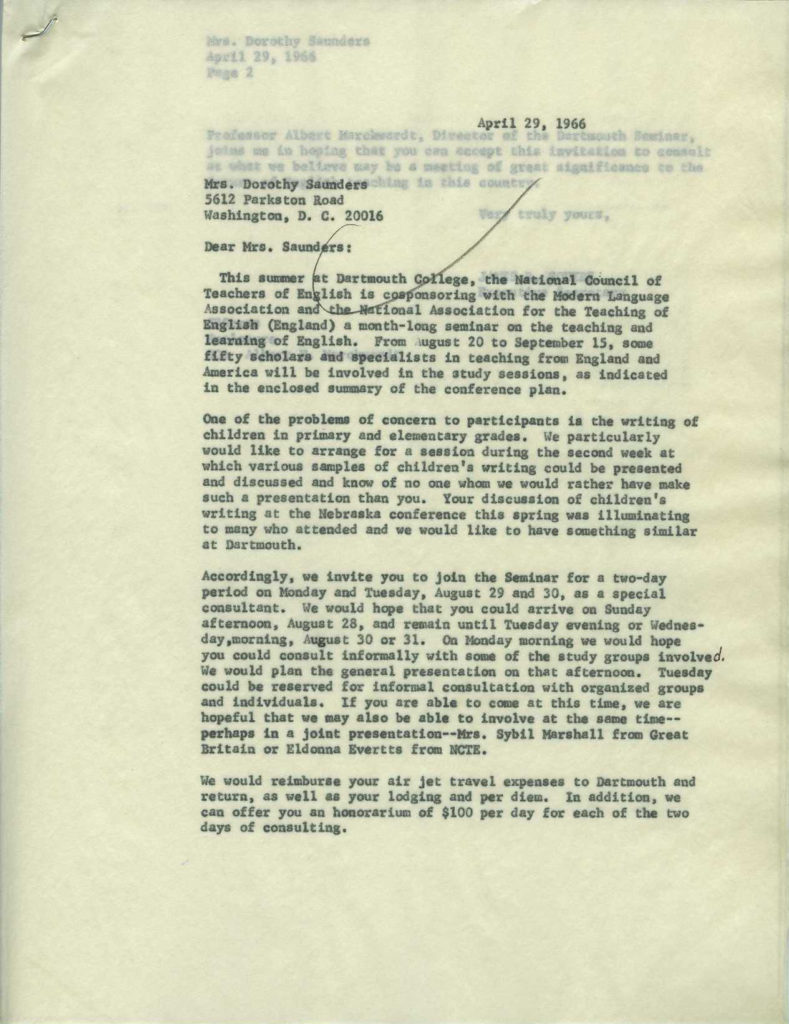

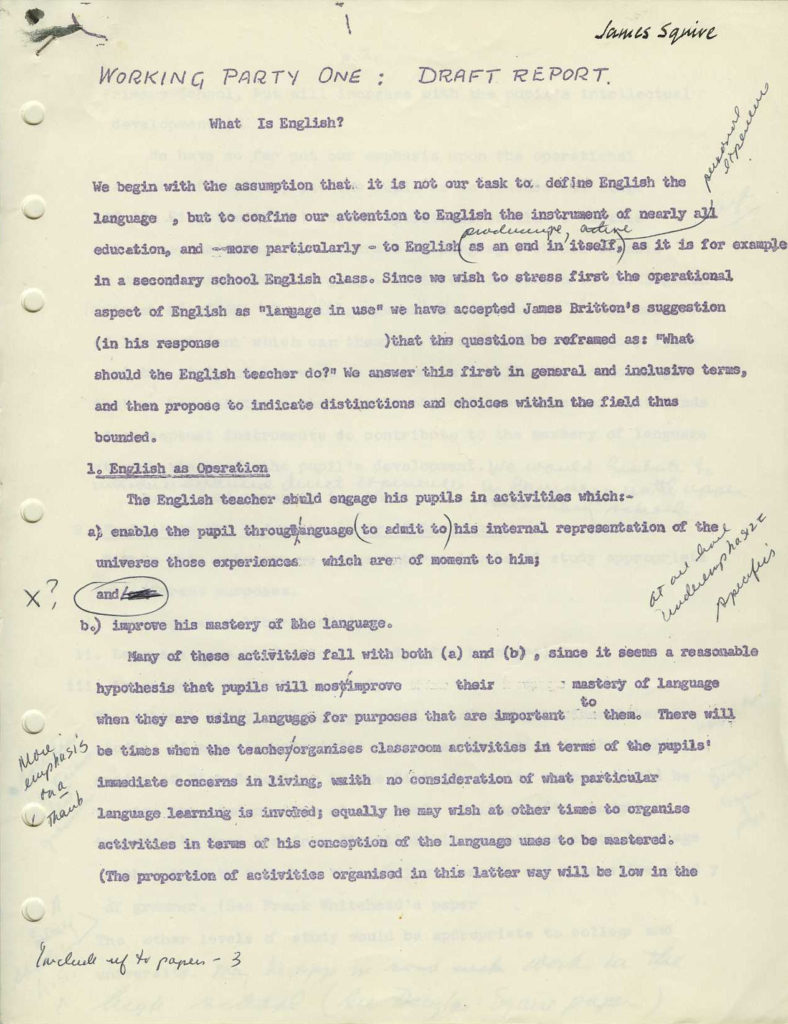

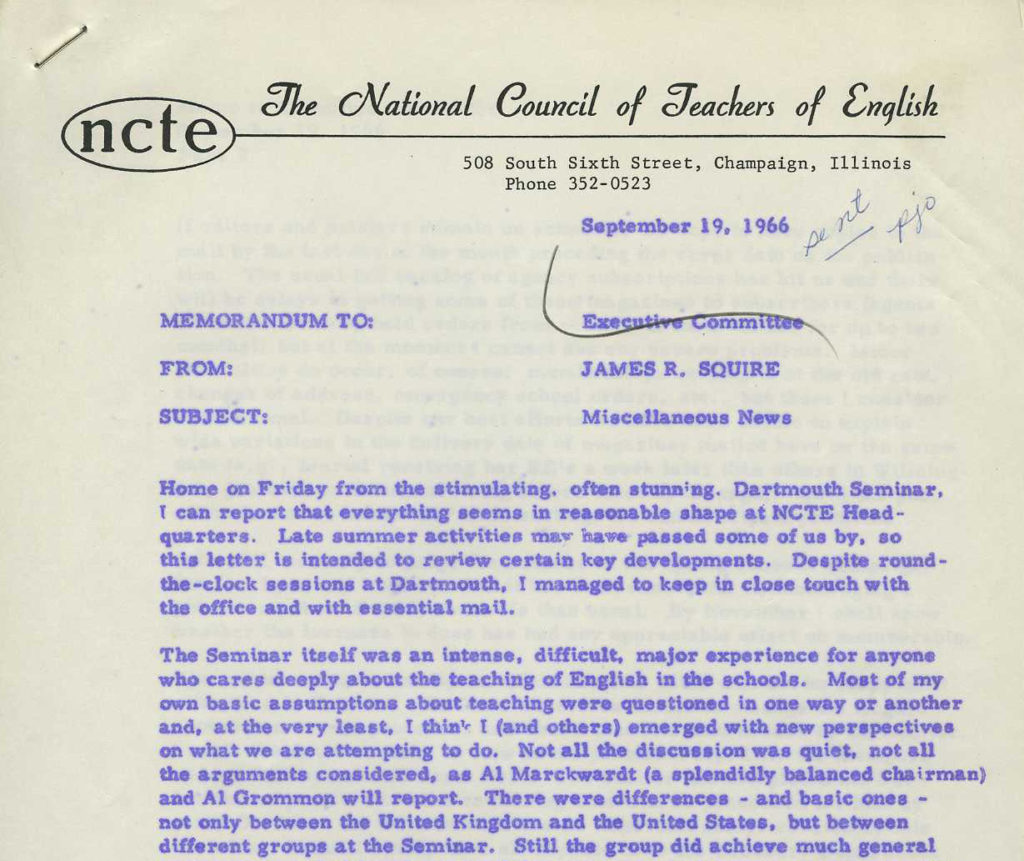

I was back in my hometown, DeWitt, Iowa, over the weekend to receive a generous award from my high school alma mater. My daughter Monica surprised me from Washington, DC, and both of us sat Thursday afternoon in a sophomore English class. It was the same classroom where I took junior English 43 years ago with Mr. Raikes. I should be more precise: the classroom is in the same place, though it’s massively transformed, along with the school around it. For example, in the last century we performed musicals on the stage in the school gym, where backstage right was filled with a weight machine. August 2016 marks the 50th anniversary of the “Anglo-American Seminar on the Teaching of English,” a landmark juncture for how English teachers in America and Great Britain viewed their subject, responsibilities, and classrooms. Participating in the month-long seminar were 21 British teachers, 24 Americans, and a Canadian, with a generous handful of consultants attending part-time.

August 2016 marks the 50th anniversary of the “Anglo-American Seminar on the Teaching of English,” a landmark juncture for how English teachers in America and Great Britain viewed their subject, responsibilities, and classrooms. Participating in the month-long seminar were 21 British teachers, 24 Americans, and a Canadian, with a generous handful of consultants attending part-time.