Work Worth Doing, Done Better with Friends

St. James Ballroom, MLA New Orleans

January 10, 2025

Doug Hesse

This is a deeply moving honor. I thank Margeret Koehler, the ADE executive committee, and Janine Utell. I thank Paul Krebs and MLA. I thank Anne Gere, Kathi Yancey, and Rosemary Feal. I thank my wife and kids, for so much time elsewhere.

Tonight takes me back to a spring afternoon forty years past, to PhD days in Iowa City. Richard Lloyd-Jones, better known as Jix, asked me to join him and John Gerber for lunch in the Union cafeteria overlooking the river. I was excited to meet Gerber, who in 1949, was the first chair of CCCC, the key organization in writing studies

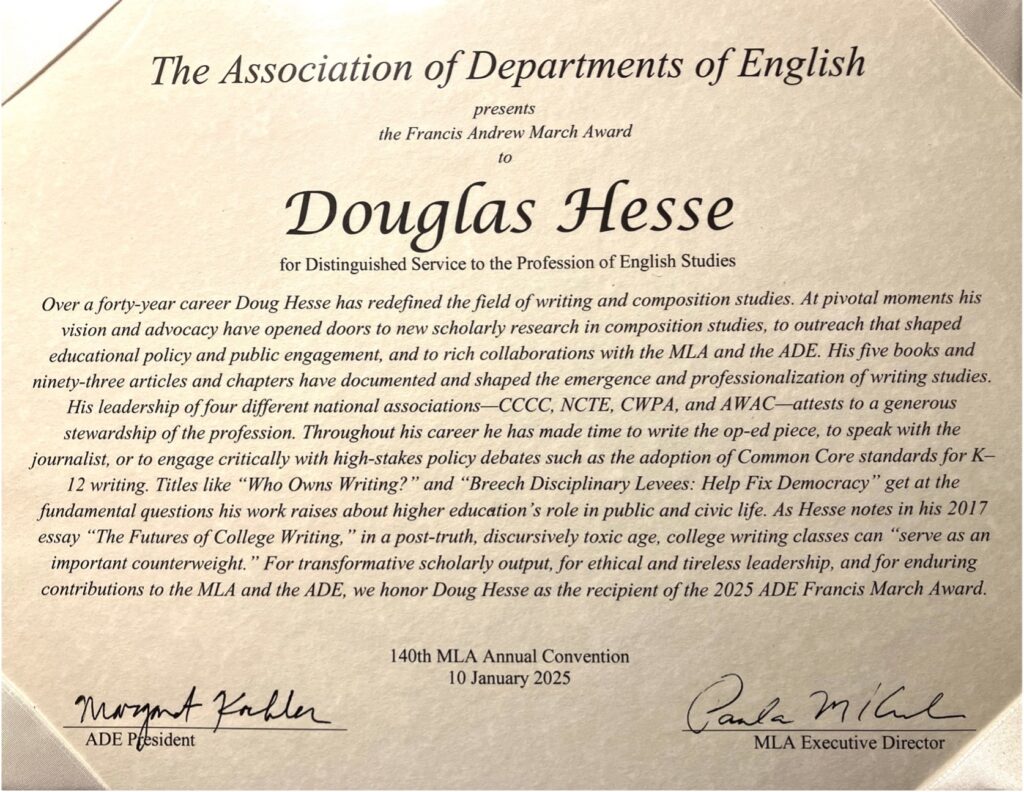

What I didn’t know then was that Gerber had just won the very first Francis Andrew March award. Jix would win the second in 1987, and I’m truly humbled to look through the list of winners since that time. Recipients with personal connections—people brilliant, generous, and kind—include Jacquie Royster, David Bartholomae, Phyllis Franklin, David Laurence, Stacey Donohue, and half a dozen more.

I’ll mention two lessons learned from such exemplars. First was a capacious vision of English studies. Gerber was a Mark Twain scholar and Jix a Victorianist, but they also championed rhetoric, composition, and creative writing. They invited students and colleagues to view all terrain in this complex ecology as worthily fertile. For example, my doctoral adviser, Susan Lohafer, was an Americanist who taught in Iowa’s creative nonfiction MFA.

My first tenure line job was in a department at Illinois State that fully embraced English Studies. The chair was Charlie Harris, who won the 1997 March award. With colleagues like Janice Neuleib, Bill Woodson. and Ron Fortune, they’d made a doctoral program whose students all took advanced seminars in literature, rhet/comp, linguistics, and pedagogy. I got to co-teach writing with my friend David Foster Wallace, 19th century nonfiction with an old-fashioned Thomas Carlyle specialist, and narrative theory with a Marxist fiction writer. We proudly advanced teacher preparation and learned from our public-school colleagues.

I’ve since watched the field dance with English studies, often in efforts safely federated into tracks, even for undergrads. I do sympathize how forces now thwart fuller integration. After all, I came to college in 1974 straight from a summer of working the back of my Dad’s trash truck. I started as a chemistry major but switched to English when I learned such a preposterous thing was allowed and, actually, unfoolish. Still, I’d like to think that even in 2025, we can make English plausible to first-generation working-class kids, including boys. Doing so requires our best rhetoric to make our passions truly account for their interests and needs.

The second lesson was to become a steward of disciplinary lands that we each merely tend for a time. Like many, I’ve tried to support people, practices, policies, and programs. I’ve tried to understand what predecessors have achieved, however imperfectly, and to see what might be moved a step ahead. Doing so has meant everything from picking up donuts for morning meetings to chairing national committees, from teaching classes when colleagues get sick to meeting with Betsy DeVoss’s staff during the first Trump administration, from leading a university gen ed revision to organizing student writing competitions whose winners met Mohammed Ali. I was always honored to be asked. I said yes as much as I could, though no doubt I was strategically stupid. Still, teaching and learning conditions need care. Someone needs to set the chairs and take the minutes, review proposals and write reports, answer phone calls from provosts, reporters, parents, and politicians.

That said, my career happened in conditions seemingly more conducive to stewardship than those of the current professional landscape, one scoured by climate change, cleft by cliffs. Precarity now seduces us to personal brands. Memberships dwindle. Reviewers disappear. The mode is no. Professional life threatens becoming a version of gaming Canvas or Blackboard sites.

I understand. Yet I humbly encourage stewardship beyond self-promotion. There’s work worth doing, done better with friends.

One morning twenty years ago, at an ADE meeting in Monterey, I came early to breakfast. Sitting alone was Bob Scholes, and he gestured to join him. I said as a sophomore I’d read The Elements of Writing, co-authored with Carl Klaus, another mentor. Scholes was gracious and recalled when he was hired by Iowa in the sixties, John Gerber was chair. Scholes, of course, won the March award in 2000. Nearly a quarter century ago, beside that California beach, its bright sky unfouled by Palisades fires, the sea of faith had no melancholy, long, withdrawing roar. There was only generous company and the wild privilege of doing something that mattered. That same kind of company is present in this room tonight, beside America’s mightiest river.

I sincerely appreciate this award and the occasion to remember so many people who have done so much for me and for our profession.