On Monday, in Delaware, I received an email from Wilson Diehl that her father, Paul, had died, and I immediately regretted having lost track of him and Dedra over the years. Paul directed my master thesis in nonfiction at Iowa, but beyond that he modeled how a professor might live a life, for a student who was a slow learner.

Paul and Dedra lived on Brookland Park Drive in Iowa City, tucked over south of the hospitals and the fieldhouse, on a short, quiet street cantilevered with tall trees. Theirs was the second professor’s home to which I’d ever been invited, the first being Dee Morris’s, who hosted my small undergraduate class in her apartment, where I met her very young daughter. Ellen, I think.

Coming to a professor’s home meant a lot to a first-generation, working-class college kid who was intimidated by all professors—including Paul. I’d met him in one of my first graduate classes in 1978, a class focusing on style and writing and including Elgin and Grinder’s Transformational Grammar. In summer 1979 he hired me to score student essays for a research grant. Thousands of Texas high school students had written arguments in response to a scenario about whether to build a recreation center. Near the end of the summer, I crawled with Charles Cooper on Paul and Dedra’s living room floor, inch-deep in piled paper. We were analyzing T-Units. That will mean something to maybe 200 people in America these days.

But none of that is the point. Paul had had childhood polio (at least as I remember now), and he walked with a slanted amble that made certain tasks impossible. One was installing window air conditioners, and he asked one summer if I might come over to carry units from the basement to an upstairs bedroom and to a downstairs window. So started a twice-yearly ritual of putting in/taking out. I’d ride my bike across town from Riverside drive, across from Mabie Theatre, propping it against a tree in their front yard. It was an orange Centurion, and later I learned that Wilson (at that time six or seven and going by Amy) associated that bike’s presence with mine.

The air conditioner operations took but five minutes, but they garnered lemonade and cookies and, best of all, conversation, welcome and reassuring time within a family like one I imagined perhaps someday to have. I deeply appreciated Paul and Dedra’s gracious, down to earth hospitality, kindness, and southern ease. Astonishment: professors could have children! And those children could be cutely precocious in all the best ways! Amy and Ethan. But Ethan is dead now, too, just recently of an infection, something Wilson let me know in Monday’s message.

After I taught three years in Ohio, I came back to Iowa City for my PhD. Dawn and I rekindled a friendship with Paul and Dedra. Monica was two and Wilson was older, and she occasionally babysat short stints. Years later, during my first years at Illinois State, Wilson stayed with us a few days in Bloomington; we met the Diehls in Galesburg for a kid transfer, and they came to our house on Towanda eventually to pick her up. But I was too stupidly busy (or so I so stupidly thought) to keep up an obvious friendship, one of the lessons I’d failed to learn from such good teachers. Twenty years after that, I met Amy again, now Wilson, in a hotel suite in Washington DC, where I was interviewed teaching candidates for the new writing program I was starting at Denver. Dense me hadn’t figured out the name until she walked into that room and introduced herself. That 30-minute interview was overladen with so much that couldn’t be put into such a circumstance. Some years after that, I read one of her essays in the New York Time’s Modern Love column.

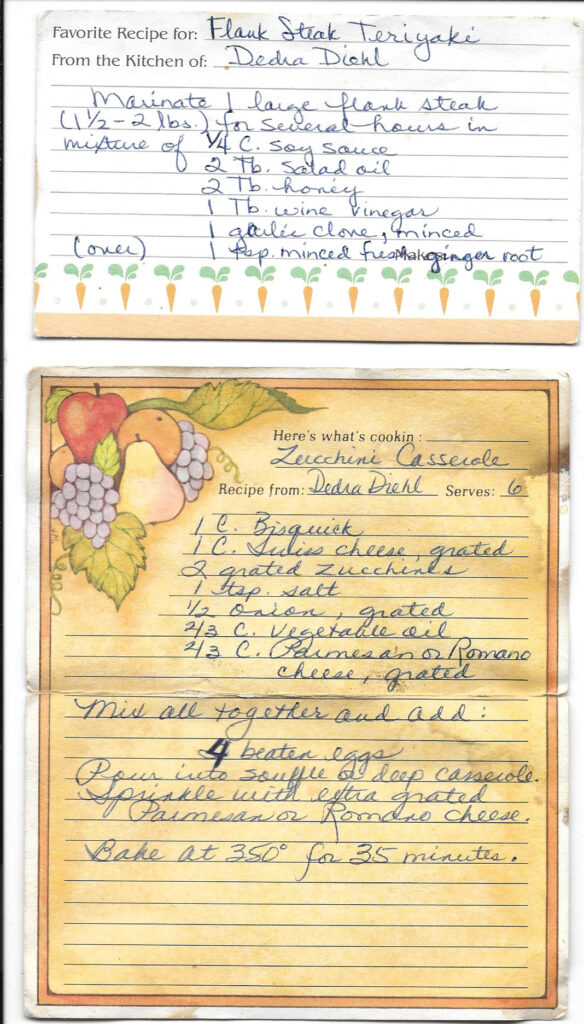

From those idyllic visits to Brookland Park Drive so long ago, one stands clearest. In my Denver kitchen are two recipe cards in Dedra’s handwriting, one for flank steak teriyaki, the other for a zucchini/cheese casserole. These are from a summer evening in their backyard, when Paul dad grilled steaks and Dedra served Pim’s Cups along with the casserole. Kids played in the grass. So much seemed easy, so much seemed possible that night under the trees. So much was, but I wasn’t paying attention. At evening’s end, we asked for recipes and Dedra wrote them on cards I’ve now carried forty years. I have those tokens of the past, and I have the distant memories, and for the latter I’m grateful. But why aren’t there more memories, and why did I misplace so much time from family and friendships to ephemeral professional pursuit? I had a mentor and model for both. I learned half his lessons, right away. Others took longer.