A month ago I bought several old books from the American Alpine Club, which has its offices and library in Golden, Colorado, in a fine building that used to be Golden High School. Pre-pandemic, I spent a fair amount of time there, ostensibly taking notes (used in a couple of pieces I published) but just as often looking at mountaineering books and magazines from decades past. The AAC has duplicates of some publications and occasionally sells them to make space or raise funds. My recent purchase, for example, included a 1922 mint condition issue of Trail and Timberline, the Colorado Mountain Club’s longstanding periodical; this particular issue was devoted to the death of famous climber Agnes Vaille on Longs Peak, during a winter ascent.

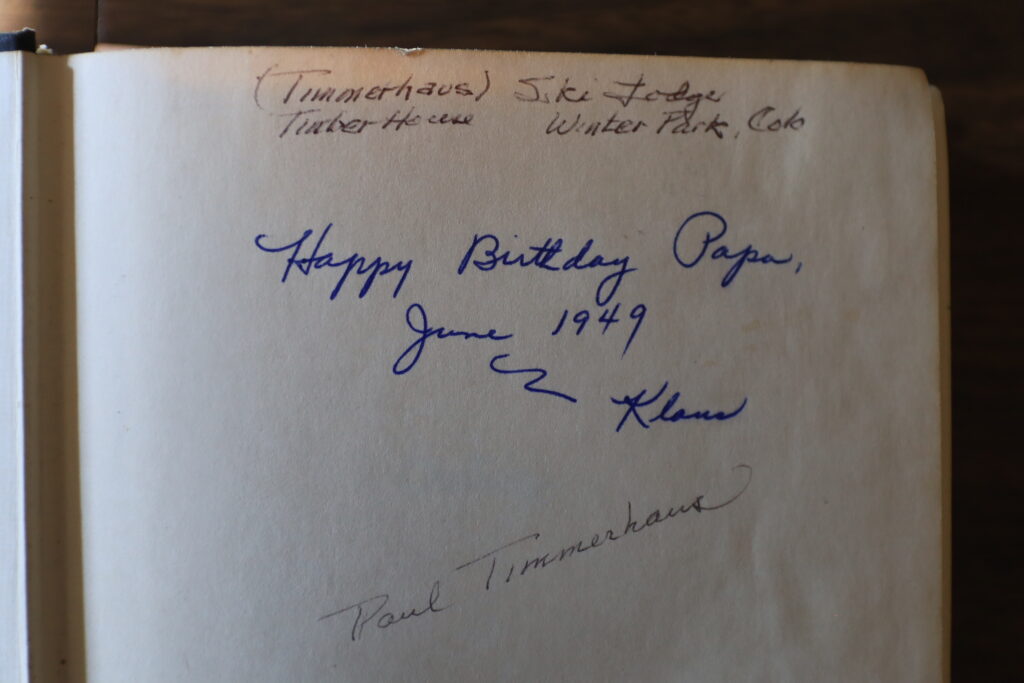

But what really caught my attention and credit card was an offhand volume, Challenge: An Anthology of the Literature of Mountaineering, edited by William Robert Irwin (Columbia UP, 1950). Written on the page facing the front cover were several inscriptions, including “Happy birthday, Papa, June 1949 ~ Klaus” and a note that the book had been on the shelves of the Timmerhaus Ski Lodge in Winter Park, CO. Curious, I looked up to find that the (now Americanized) Timber House Lodge still operates, with its most usual description being “unpretentious,” just a notch above the fear-inducing “rustic” or the more ambiguous “quaint.” Paul Timmerhaus owned this namesake lodge, and Klaus, his son, was a noted Professor of Chemical Engineering at the University of Colorado. In 1949, he’d have been working on his degrees at The University of Illinois. This was all interesting stuff, and as someone who rarely minds chasing textual threads (or procrastinating), I enjoyed sleuthing.

Then I noticed something more remarkable.

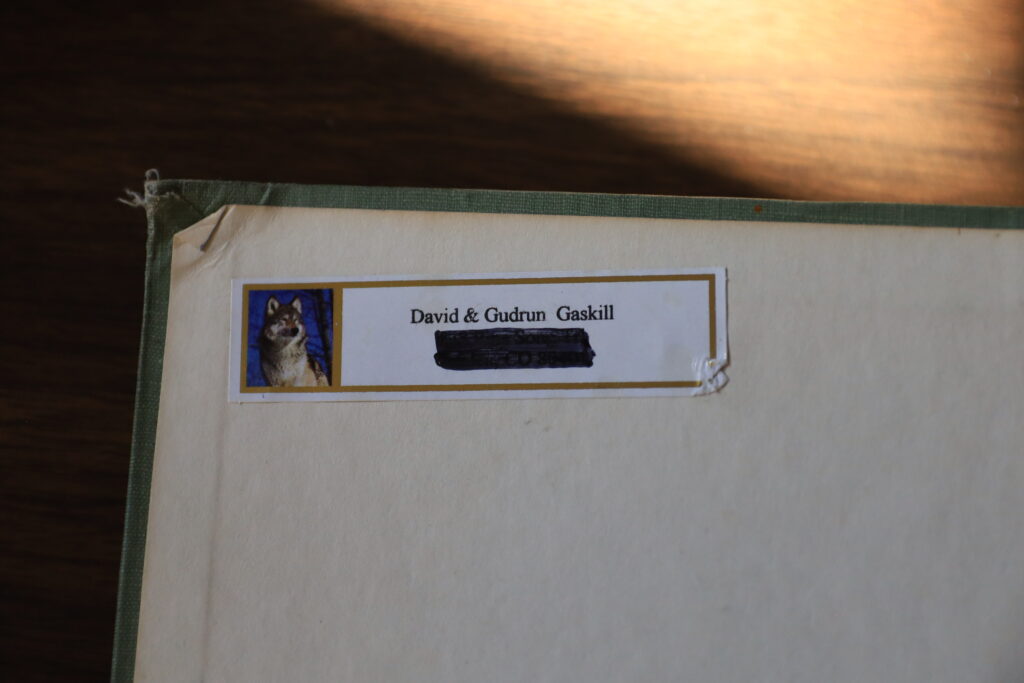

Inside the front cover was a small address label, the kind I get every other week from Defenders of Wildlife or the Audubon Society or St. Jude or Unicef as a teaser to donate. The names: “David & Gudrun Gaskill.” I recognized I was holding an even more interesting piece of Colorado History. Gudy Gaskill, whom the Denver Post memorialized as “a force of nature,” is revered as the driving energy in forming the 567-mile Colorado Trail. I’ve been at the bridge and Trailhead dedicated to her, on the Middle Fork of the South Platte River, between Foxton and Deckers. It turns out that Gudy was Klaus’s sister. I speculate she got the book from her father at some point, then donated it to the American Alpine Club at some other point. I was holding a book she’d owned. Very cool.

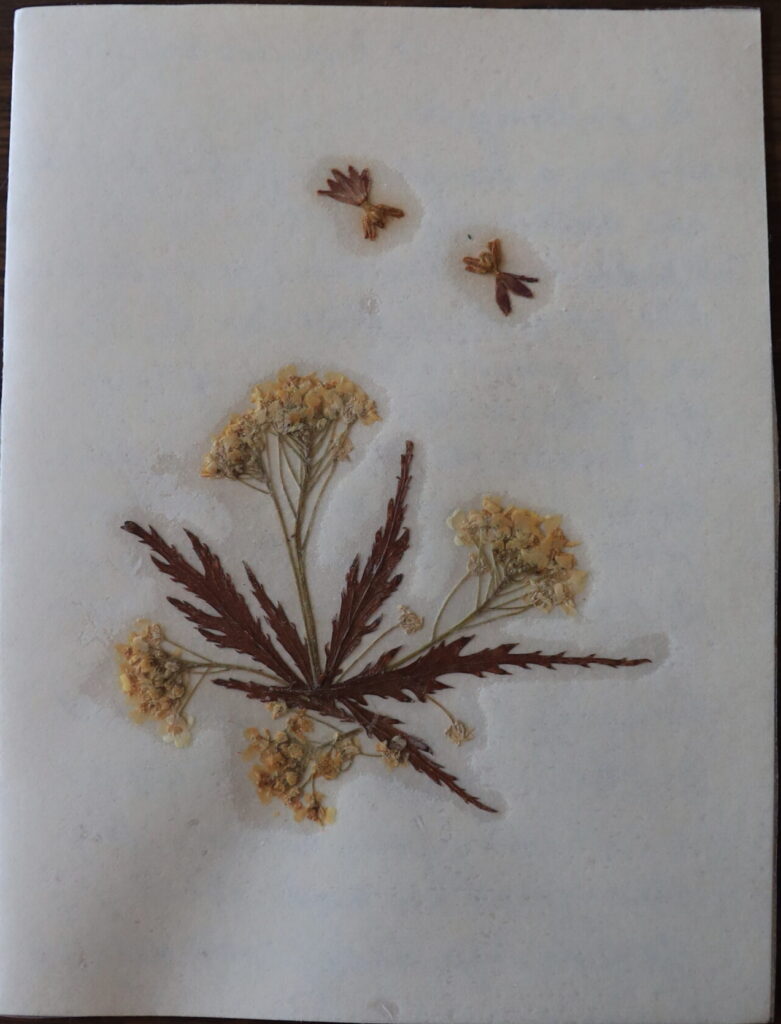

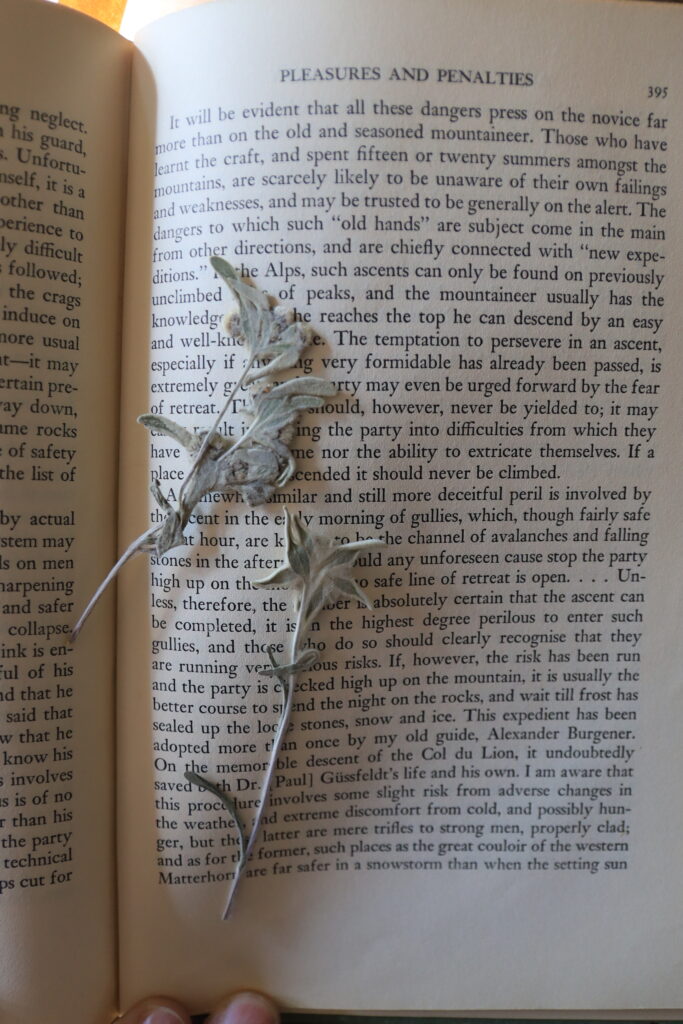

Then I noticed something even more remarkable–something to the theme (finally) of this essay. Flipping through the book, I found dried flowers pressed between pages 394-395. They were ghostly white, with faint tinges of green and blue, though maybe my imagination and desire have projected color where there was none. A far more skilled naturalist than I am could probably identify the flowers–along with other ones pressed between pages 24-25, 120-121, and 152-153, all the same species.

Who had placed them? I’d like to imagine Gudy Gaskill hiking a high Colorado meadow in the Lost Creek wilderness, picking striking flowers, moving them from her pack to the heavy pages of Challenger. Maybe, she’d had dozens of flowers, and over time the best had been replucked and repurposed for letters or shadowboxes. These were but remnants. Or perhaps Gaskill had idly thumbed the book over the years, each encounter with withered blooms reminding her of that high mountain day.

Of course, it’s just as likely a summer guest at Timmerhaus had picked the flowers along Cooper Creek in Winter Park and pressed them, with great intention, into the heaviest book he found in the lodge library. But in the hustle to make the train back to Denver, he’d forgotten. Perhaps knew, even at the picking and the pressing, that whatever floral essence might remain would mockingly fall short.

Or, just maybe, the thought all along was to leave wispy smiles to future readers: to the family from Omaha to Gudy Gaskill to me. Instead of millennia-dead people chasing around Keats’ Grecian urn, here were fragile traces of life–plant and picker/presser–long gone yet preserved.

About this time, I received a card from Ann Arbor, Michigan. I’d sent my longtime friend Patti Stock some postcards printed from my mountain photographs, and she was replying in creative kind. Actually, Patti had gone better, for her card, pictured in the first image atop this essay, was fronted by a pressed flower, still brown, still yellow, held against paper by some film and process I couldn’t figure, delicate and whimsically strong.

But it wasn’t just any flower, any card. Patti’s letter inside told how her mother had fashioned herself a flower press, now passed on to Patti. With the press were flowers her mother had saved, and with them these were still a few cards Mom had fashioned, years ago. Patti trusted one of those cards to me. I was delighted and honored, humbled and a little choked.

My father passed away three months ago, following my mother by a year, leaving my sisters (mostly) and I to go through countless boxes of ephemera: photographs, of course, but also diaries and documents and knick knacks and bric a brac from wooden duck decoys to a set of straight razors from a grandfather’s barbershop, Dad’s Dad killed on Christmas Eve when Dad was eight. There were letters and school programs and Mothers Day cards and birth announcements and old tickets and locks of first haircuts: a vast welter. Much of it was loose, occasionally clumped by rubber bands, occasionally thematically congregated. An impressive fraction was gathered into albums and scrapbooks, sometimes with captions, sometimes not. In my sister Joellyn’s living room, we paged through 90 years of two lives, a small portion put into order, on one hand colorful and vibrant, on the other fixed and faded. It was plucked and dried from Mom and Dad’s full lives, each photo or artifact a flower gleaned from vast meadows of experiences gone, gone, gone. Mom and Dad had preserved scattered flowers of decades. Now they’d come to the children.

One could call this foolishness. How vain to hope that this columbine or that cinquefoil, pressed into pages–into memory–could at all capture that bluebird day when white aspens stood against the quartz outcropping, when the Cooper’s hawk whimpled and the mountain drew your heart up a still-snowed couloir! How desperate to put pretty flowers in the flap of a backpack! To what end, really? Desperation? Common advice about pressing flowers is to choose ones with low moisture, even if they’re a little less colorful. In drying faster, they retain more of whatever color they have. Lusher flowers desiccate to brown. A sensible person, then, would go for the dull, knowing the futility of trying to keep the vibrant. A sensible person wouldn’t, in fact, put plants in books or presses.

Still.

The goal is never perfect rendering. Justice to life as lived is impossible, and that’s not the point. When I’m surprised by Gudy Gaskill’s flat alpine vestiges, when my breath catches at Patti Stock’s card with her mother’s embodied hand and heart, I’m moved not because they are perfect but because they exist at all, because a particular person at a particular moment decided this I’ll preserve, however hopelessly inadequate, imperfect, and ultimately dimmed. It is the care and the caring.

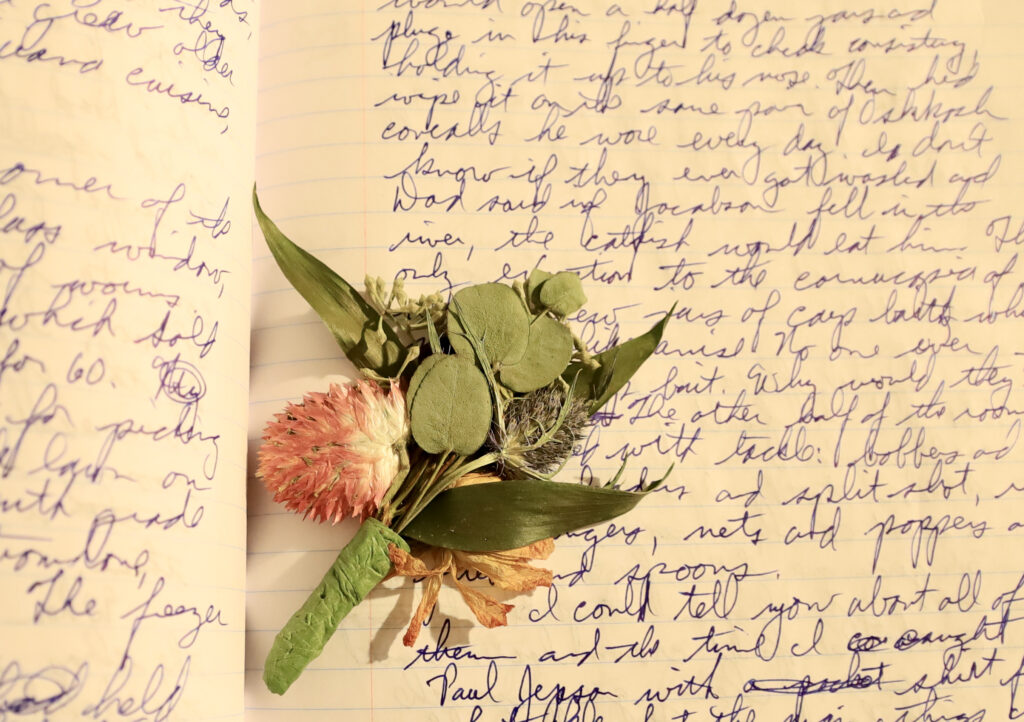

The evening my father died we were celebrating my youngest daughter’s wedding, a thousand miles away. We’d known from sisters back in town that he was down to final hours and I’d left a lengthy phone message that I’d like to imagine Dad heard when Joellyn played it. I learned near the end of the dance when he passed. Late that night I pressed my boutonniere between the pages of a notebook I’d brought with me, and three months later this morning I looked to see how they’d dried and what colors remained.