Thoughts on advocacy as education in troubling, hopeful times.

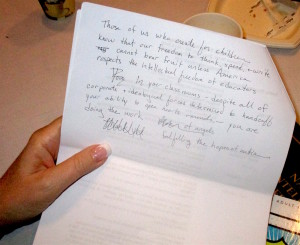

[Above: Laurie Halse Anderson’s revisions, explained below.]

NOTE: Another in a series of completely unofficial, personal musings in a year spent as president of the National Council of Teachers of English.

I’m thinking quite a bit these days about advocacy, these wintry days when a group of armed men have taken over a public building in Oregon to further their cause. I’m thinking about advocacy because on January 10, I’ll be speaking on a joint NCTE/MLA panel at the Modern Language Association Meeting in Austin, Texas. I’m thinking about it because the Call For Proposals for #NCTE16 is due on January 13, and Susan Houser has set our theme as “Faces of Advocacy.” I’m thinking about it because at the end of January, the Subcommittee on Policy and Advocacy convenes in Washington, DC, to write the 2016 NCTE Educational Policy Platform. I’ll say more about these below.

First, however, some thoughts about the point of all this energy.

In her eloquent remarks upon receiving the NCTE Intellectual Freedom Award, writer Laurie Halse Anderson concluded that “Those of us who create for children know that our freedom to think, speak, and write cannot bear fruit unless America respects the intellectual freedom of educators.” I asked Anderson if I might photograph the last page of her script, because I’m always fascinated by a writer’s process and by the material presence in her own handwriting. That picture’s above. You’ll see that the final version of her remarks differs from even her last-minute revision.

I was heartened, then and now, by Anderson’s reminder that artists “are called to do more than simply document or analyze” and that “we must imagine the next reality, the America that truly welcomes and cherishes all of her children.” This last imperative carries the sobering assumption that we don’t truly welcome and cherish all children.

Now, I can sadly imagine that, in fact, there might be some citizens who consciously assert that some children should, in fact, not be welcomed, let alone cherished. I have to believe those folks are decidedly few and mostly ostracized. However, I can easily imagine that what constitutes “cherishing” differs widely among different groups of people, all of whom have the best of intentions and hopes. We see these differences when dubious school reforms, curricula, and pedagogies are proposed—dubious because they’re supported neither by the research base nor the experiences of professionals in the field. But “dubious” does not mean “malicious.”

We have to see advocacy, then, as education. We have knowledge—hard earned, rigorous knowledge—that others don’t have. We need to teach others to whom we should attribute good intentions—even if they’re uninformed or misguided. Like lots of teaching, this is tough work, especially when “good intentions” are shaped by ideology and selective viewpoints.

Along the way, we need to assert the vital importance of the creative and imaginative as part of literacy learning. That was an important theme of Laurie Halse Anderson’s remarks and one to which I’ll turn in future postings.

Each January, NCTE’s Policy and Advocacy Subcommittee meets in Washington, DC, to draft the organization’s annual educational platform. (I chaired this committee last year and am a member this year.) This broad document sets out broad principles of what the Committee believes can be achieved in the upcoming legislative year. The group spends a day meeting with legislative leaders (in 2015, including for example, with the chief educational aids of both Senators Lamar Alexander and Patty Murray) and with selected other educational leaders (including, for example, in 2015 people from the national PTA and the Chief State School Officers). If you look at the 2015 Platform, you’ll find that we had considerable success, particularly in shaping the revised Elementary and Secondary Education Act that was recently passed.

Advocacy at the federal level is important, of course, but all of us realize that most of the real action occurs at school/campus, district/system, and state levels. Affecting change there is a considerably more diffuse enterprise, and NCTE has gathered a set of resources at http://www.ncte.org/action.

This weekend at MLA in Austin, I’ll appear on a panel with NCTE Executive Director, Emily Kirkpatrick, with MLA Executive Director Rosemary Feal, and with Roland Green, MLA President. I’ll share my remarks, but I’m most interested in the relationship between the national and local levels.

From Denver,

Doug